Collectors of historical flasks so far have had no more occasion to worry over fakes than collectors of cup plates. There have been too few to cause real trouble. The reason probably is that there are fewer buyers of flasks and cup plates than of pattern glass. To be profitable, the production and distribution of fakes necessarily depend upon a wide popular demand. That is why at the present moment, reproducers are largely concentrating on pattern glass. Fads and fakes always go hand in hand.

Some years ago when the craze was all for the more primitive forms of American antiques, it was natural that non-discriminating fans should go in heavily for any old bottle that looked appropriate on the shelves of well-worn pine corner cupboards, or on the “period” mantels of dining rooms that aped seventeenth-century kitchens. The true collectors of historical flasks were, of course, a different class. They had the valuable help of Mr. Van Rensselaer’s “Check List” of types, classifications and attributions and, move over, sought and paid high for color and beauty as well as for rarity.

For the mere faddists, any old-looking bottle sufficed, so they bought medicine vials, ink and bitters bottles; demijohns and pickle bottles and jars, large and small, and even huge carboys that had held acid, which, of course, was in harmony with the old-pine interior, as the Pilgrim Fathers habitually kept their supply of rum close to the hearth. Buyers were told, in strict confidence, that they must always look for the “ponril mark,” which not only was the infallible test of antiquity bur accounted for the high dollar values. The effectiveness of such pieces in creating the desired “atmosphere” was accepted without question by many of these American devotees.

At a quite early stage of the antique boom, large new pickle jars made their appearance. These were not necessarily copies or close imitations of old ones, but they were useful as flower holders, just as the smaller pickle bottles were made to serve as lamps. The electric light bulb, of course, reminded the proud owners of the lighting devices of the Mctyflower’ s passengers!

Among the earlier bottle reproductions was the tall log cabin Plantation Bitters, which was made in a beautiful blue and in a bright green. These were intended to be electrified for service as lamps. While they were doubtless copies from the well-known Drake’s Plantation Bitters bottles, they did not have the blown letters of the original and no collector could have been fooled. Indeed, I do not recall that dealers ever sold or tried to sell them as old.

An active demand necessitates an adequate supply, if dealers are to stay in business. The moment genuine old bottles were no longer to be found in quantity in the old attics and virgin cellars that had been fine-tooth-combed by pickers and collectors, it became necessary to fall back on imitations and reproductions to supply the demand. After the fake pickle bottles and the Plantation Bitters, the first of the historical flasks appeared.

Curiously enough, the makers selected one of the cheapest and most common of all the flasks in Van Rensselaer’s Check List: the Cornucopia-Basket of Fruit flask. It may be doubted whether the makers actually intended it to be passed on to collectors as an antique, for it had an ornamental glass stopper and, in many gift shops, specimens were seen with gilding or hand-painted decorations in color.

It would have been truer to form if the makers had furnished instead antique corncobs or discolored wooden plugs. Also it did not have the scarred base of the old ones. The new flasks came in a shade of reddish-brown amber which was not found in the originals. Most of the early Connecticut and New Hampshire bottles were made of inexpensive glass, and the olive-green, olive-amber and yellowish-brown amber in which the old flasks come may possibly be a more difficult color to imitate today than the amethyst, blue or puce for which collectors paid very high prices.

The new Cornucopia-Basket of Fruit flask did not sell well either because it was too common a pattern for a fake or because it was not pushed intensively. Not very long ago, one of these bottles, ornamental stopper and all, was sold as old at the auction sale in New York of a famous glass collection.

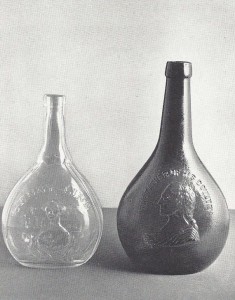

Copies of the so-called violin bottles were soon seen in many colors, such as ruby-red, sapphire-blue, amber, etc. The colors are too vivid, and the glass much too heavy. These and the new high shouldered Sunburst bottles were made on order for a man in Boston. The initial of his last name, “M,” may sometimes be discerned in the base of both bottles. The new mold carried this letter in it, but the scar left by the punty rod usually obliterated it, so it is rarely ever found today. The Sunburst bottles are good copies in some respects except for the usual flagrant errors; the glass is too clear; the colors too vivid and the glass usually, though not always, too heavy. Moreover, neither flask was made in red originally.

A quart flask having a cluster of grapes on one side, with an eagle on the reverse, in amber and in other colors, is frequently seen in gift shops. They are priced as low as $2.00. Originals are worth $15.00 in aquamarine and in amber would be worth more. I have seen them listed wholesale at $1.00.

A quart Washington with Eagle and 12 Stars has been reported in deep blue, which the owner describes as crudely blown. It was apparently produced from a plaster mold. During the 1920′s there appeared the Jenny Lind calabash bottle bearing the inscription FISLERVILLE GLASS WORKS. It was made in Haida, Czechoslovakia. A definite effort was made to copy the original, which, incidentally, never was a high-priced item, selling at from $5.00 to $10.00 in aquamarine.

All varieties of Jenny Lind bottles were fairly popular years ago because they were easily identified with the period of the Swedish Nightingale’s visit to America. That made them old enough to be considered antique by young collectors. Some unscrupulous dealers bought the reproduction and passed it on to customers at a profit of 300 per cent or better, but many more bought it believing it to be really old, because the pickers and runners who peddled them went to the trouble of carefully “antiquing” them with oil and inexpensive dirt and wear marks.

All over New England, Pennsylvania and New York pickers planted many of them in barns and hen houses and showed many an honest farmer how to double his money the next rime city slickers came around to rob him of his family heirlooms. The imitation differs in certain details from the original, but only a specialist in bottles would notice them. The neck, for example, does not raper quire like that of the old, and there are minor differences in wreath, bust and base, which may be detected, provided you know how and where to look.

This particular fake did a great deal to kill the demand for all Jenny Lind calabash bottles. It is still found today in small shops, whose owners, unfortunately too numerous, believe that the customer should pay for the ignorance of dealers who bought as genuinely old what later turned out to be new and of little value. The importers state that the Jenny Lind calabash is no longer made but a few years ago plenty of them were selling at 50¢ each.

Following the Czechoslovakian imports, a second edition was produced in South Jersey, in vivid shades of purple, emerald green, amber, and sapphire blue. The most startling one to come to light was shaded from red to amber, somewhat in the effect of New England’s amberina. This particular variety of a Jenny Lind calabash bottle also carried, on the reverse side, a view of the Fislerville Glassworks.

There are two rather simple ways of distinguishing the new ones from the old. The copies have a pomil mark in the base which appears to have been stamped on, instead of the familiar rough scar left when the bottle was broken from the pontil rod. These rough scars are often sharp enough to cut the finger, but with most of the reproductions, the pontil marks are just fairly smooth, round depressions, of ten not even in the center of the base. The original Jenny Lind bottles have a fairly good-sized neck which rapers toward the top. The reproductions have a more slender neck which rises in straight lines, without tapering, from the body of the bottle. The modeling of the design is poor.

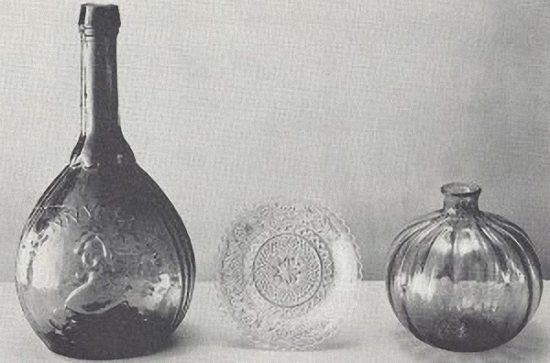

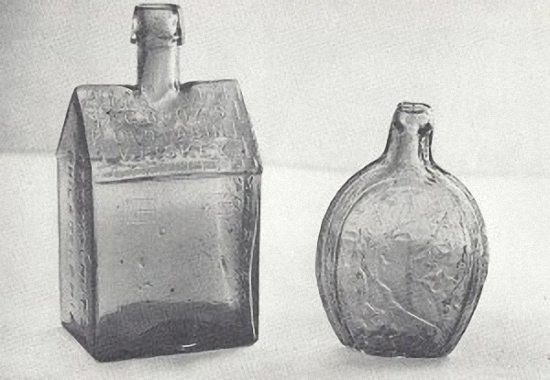

The timed melon-shaped bottle is similar to an early Ohio type. The new one illustrated is Mexican, aquamarine in color, and filled with more tiny bubbles than would be found in old Ohio glass. There is little attempt to deceive, so far as the pontil scar is concerned, for the mark on the base shows only a faint round stamp. These bottles were sold in gift shops years ago, at $1.00 each.

A still later reproduction that sold fairly well until its spuriousness became a matter of common knowledge, was the flask with the Horse and Cart and the inscription SUCCESS TO THE RAILROAD. In some respects it was a good copy, but the makers again blundered on details and made it easy to distinguish it from the authentic.

The most important of these were in the curve of the neck of the horse and particularly in the mane, which consisted of sharply defined short hairs that stood straight up. You could feel them with your fingers. Some dealers ground out the telltale mane but the marks of the grinding wheel show plainly.

Of several variants of the authentic Horse and Cart flask, in all but one of them the mane droops over the side, as a decent horse’s mane ought to do. The importer informed me that the mold cost $200 to make. Original Horse and Cart flasks are fairly common in various shades of amber but quite scarce in aquamarine. The new ones were made in several other colors in which originals never have been found.

Some time later, reproductions of the once greatly coveted. E. C. Booz Old Cabin Whiskey 1840 bottle made their appearance. Rumors have it that an old glass blower in South Jersey found one of the original molds. This story is seriously doubted. If actually really true, it was reconditioned. More than likely a new one was made and so it became possible to turn out large quantities of Booz bottles.

The original was a product of the Whitney Glass Works, not very far from where the reproductions have been made. The old bottles once sold as high as $150 for the amber and $300 for the green, but they never were justly entitled to the popularity they enjoyed because their history was based upon errors. One was the mistaken theory that the bottles were made during the Log Cabin and Hard Cider campaign of 1840.

Again, it was asserted that the word “booze” was derived from the name of the Philadelphia whisky dealer, Mr. Booz, though as a matter of fact it was Elizabethan English. Despite the fact that the reproductions were made from a good mold, the quality of the glass betrayed their newness in the amber specimen and in the shade of the color in the green. Moreover, there was no period after the word “Whiskey,” as is found in the old.

Before it was generally known that it was being reproduced and honestly sold by the maker at reproduction prices, a number of experienced dealers paid high for the copies. For many years a brisk demand had existed for the Booz bottles, showing the persistence of error, because it was the myth that sold them.

The price subsequently fell considerably from the boom-time top. Today it may be doubted whether any but an inexperienced collector would have the courage to pay more than a few dollars for a genuine Booz bottle. About twelve years later a reproduction of the Booz bottle with the roof ridge beveled at the ends appeared. It is a very poor imitation.

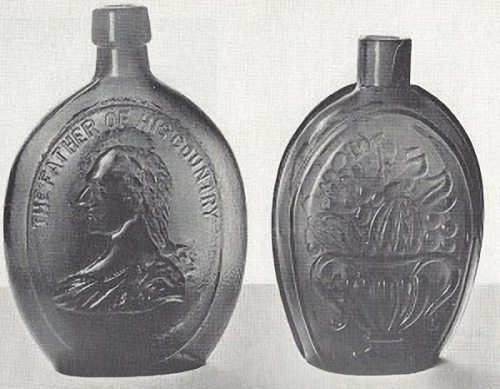

The pint flask shown has a bust of Washington with the inscription, THE FATHER OF HIS COUNTRY on one side and exactly the same on the reverse. No such bottle exists among the genuine historical flasks. The color in some is almost the smoky shade of the cheap sunglasses sold in the “five and tens,” and the surface is rough, almost crinkled.

Possibly it was intended thereby to differentiate it from ordinary smooth-surfaced commercial containers. The bust is not a good copy of any seen on the old Washington flasks. The hair, the nose, the flat base and the lettering betray the newness the moment you look at it. Since it is obviously not a reproduction, it may not be fair to class it with the fakes. In 1932, the bicentenary of Washington’s birth, many commemorative articles came on the market, among them being the quart bottles sold in chain stores as vinegar containers. These displayed a bust of Washington.

The novelty Washington bottles were too unattractive for the gift shops to handle successfully, while antique dealers and pickers refused to buy them because no one could mistake them for old, was also made. It was even worse as a reproduction. The neck is too thick; the base is flat and the bottle is larger than the old ones. The glass is the same as in the flask. It is seldom one finds either of these on sale in any kind of shop today, though occasionally they appear on dealers’ lists, without enlightening descriptions.

Later came a pint flask with a bust of George Washington and the inscription WASHINGTON on one side and on the reverse, a bust of Taylor with the inscription GEN. Z. TAYLOR. It was made in Haida, Czechoslovakia, where the Jenny Lind, Fislerville, calabash reproductions originated.

Again serious mistakes were made, easily recognizable by anyone familiar with authentic historical flasks. The busts show differences and, moreover, the flask was produced in colors that are not found in the old.

These strange shades, instead of inducing purchases, really put otherwise unsuspecting collectors on their guard. This particular flask, when genuine, usually comes in aquamarine and is seldom seen in any of the colors which other varieties of old Washington-Taylor flasks show. Of course, inexpert collectors unsuspectingly bought the new ones. Its chief accomplishment has been to make both collectors and the smaller dealers skeptical about the authenticity of many genuine flasks. After all, it is not always easy to distinguish fakes from originals. The importers say they have discontinued this line but they are still offered for sale at the smaller shops.

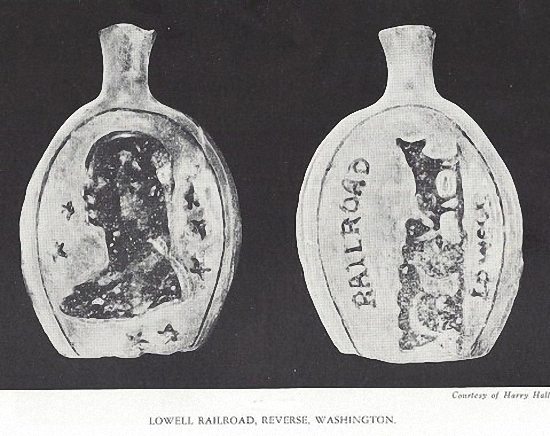

A still later fake is a half-pint with an outspread eagle on one side and on the reverse, a Horse and Cart, lettered LOWELL and RAILROAD. It certainly is not a true reproduction made from a good new mold. It resembles the fakes that turned up in Philadelphia a few years ago, made from plaster of Paris molds. The Lowell-Railroad half-pint is very crude, so badly misshapen and blurred that it could not possibly pass for authentic.

Nevertheless, some dealers bought them. As a rule they sold at a very low price. Most of them are light green with a slight yellowish cast, but they also come in shades unlike any seen in the original, which were mostly olive-green or the familiar golden-amber. One turned up in a brilliant sapphire blue. Another Lowell Railroad half-pint “variant” has a bust of Washington on the reverse. No such flask was made originally. It cannot be called an imitation. These are the crudest flasks ever made. They were produced by an individual workman in New Jersey, in the 1930′s.

The experiment of using plaster of Paris molds to make flasks is not new. Years ago, a few of these crude, misshapen, poorly impressed flasks made their appearance in some of the Pine Street antique shops of Philadelphia. Before that, I had seen a quart in a deep opaque-blue in a New York shop where it was held at $150. A well-known collector has a half-pint of the Albany Glass Works, Washington on one side and a ship on the reverse, and also a quart, Eagle, with cluster of grapes on the reverse.

The latter was found in a Pine Street shop by another famous bottle collector. The dealer from whom the fake was bought told the collector that the man who made it was a workman at a glass factory in New Jersey, not very far from Philadelphia, who blew it after hours out of impure glass, which cost him nothing. These pieces were made in all sorts of freak colors, for the blowers used what was left in the pots at the end of the day.

Probably the best copy of an old historical flask is the Dyottville, Washington-Taylor. However, even this one should not fool a discriminating bottle collector. The colors are not only exceedingly poor, but the pontil mark on the base has been molded in, instead of being left scarred. The distinguishing feature of the reproductions is the difference in the inscription PHILADA. On the originals, the a is smaller than the other letters and it is not on the same line with them. On the reproductions the letters are uniform in size and on the same line.

The only fake historical flasks which are sometimes sold as original by unscrupulous dealers. Of course, there are also the large Cathedral pickle jars and the Moses type of Spring Water bottle in a beautiful green. The latter can be obtained in the same green glass that was used to make reproductions of the large barrel-shaped bottles which, years ago, came to this country from France with some sort of tamarind preserves. Glass pieces of this type are used by interior decorators in certain color schemes. They have been converted into lamps that are decidedly attractive. I once saw a very large demi-john, in the inside of which was an elaborate cluster of small electric bulbs. It undoubtedly took time and skill to electrify that chandelier.

No attempt has been made to include the reproductions of “freak” bottles, like glass cigars, revolvers, busts of persons known and unknown to fame, etc., since the oldest of the originals are not very old. All of them, new or old, are priced too low to make it worth while warning curio buyers.

The flask collector has not had much to worry about. The imitations of the early blown diamond-quilted and other such patterns did the most harm and they are treated and illustrated here.