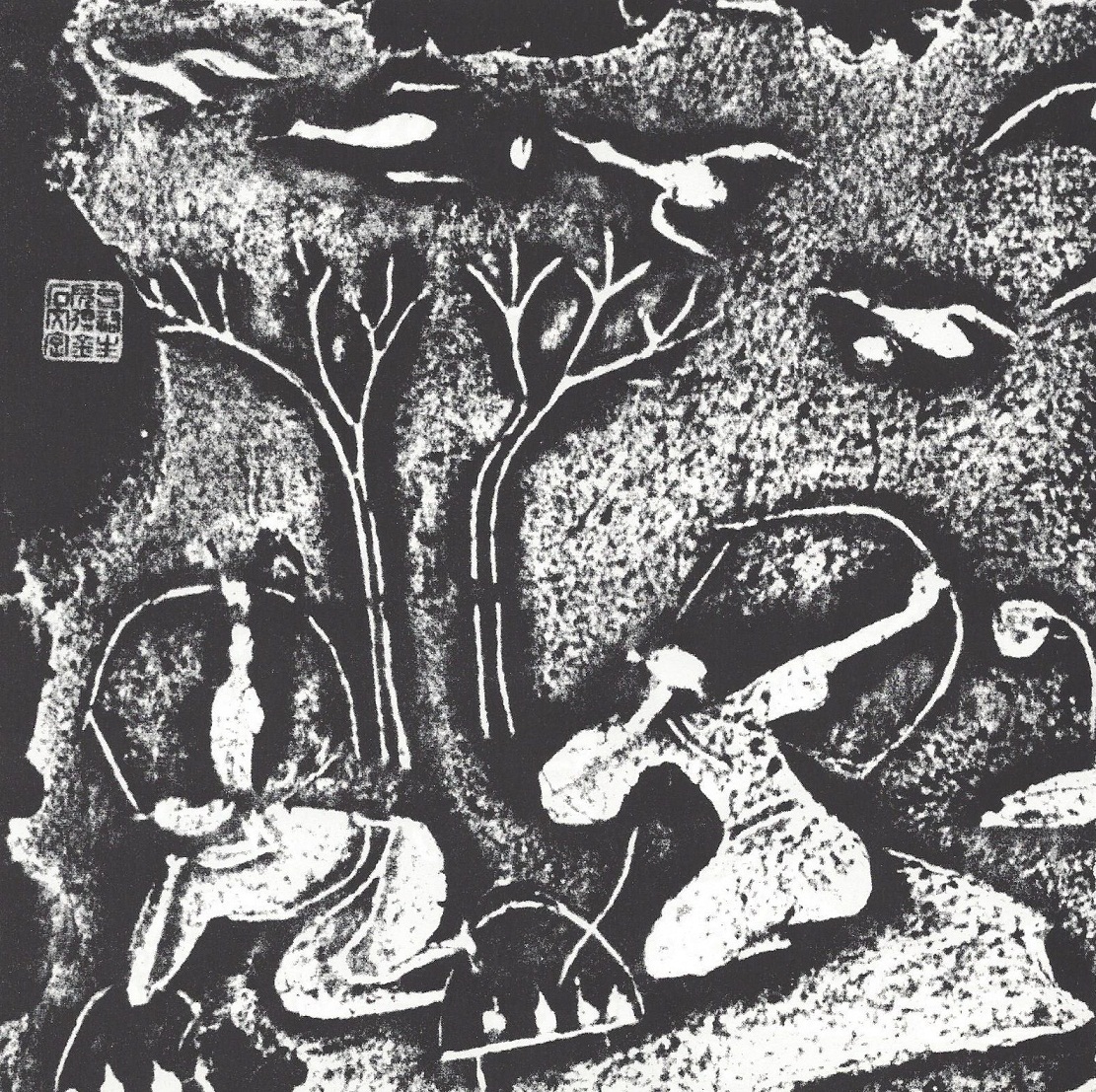

The traditional components of ancient Chinese society under the supreme ruler were the great lords who governed the land in his name, the knightly gentry who populated their courts arid fought their battles, and the peasants who provided the necessities of life to all classes. Outside this class structure, and therefore hardly recognized as true men, were merchants, artisans and slaves.

For the aristocrats, both great and small, life could be a rich and splendid affair. But for the man at the bottom, life was poor and changed little. The nameless farmer, grubbing in the yellow earth, continued to labor in misery.

The elite always knew that they could not live without the farmer and believed that reasonable attention should be given to his welfare. But no one suggested that lie should be treated with honor, he was a necessary instrument, to be kept in trim without pampering.

The peasant was seldom an independent farmer. Occasionally one or another government would give him a field of his own, but the arrangement was usually short-lived. When civil disorders and invasions by nomads from the north weakened the structure of society, strong feudal lords extended their control over nearly all the land, great manors grew unchecked, and the farmer was forced to become a tenant again, and sometimes even a serf.

Despite the poverty of his life down through the ages, there were some gradual improvements in the condition of the farmer. For instance, he got better tools. The horny-palmed peasant of the Bronze Age had only a wooden hand plow (if he was lucky, it had a bronze share), a simple hoe and a reaping hook. But a tenant of a feudal lord of the Fifth Century B.C. might own a plow with an iron share, and perhaps ah old ox to pull it. With this equipment, farmers improved the soil so that it retained rainwater more efficiently, made better seedbeds and resisted weed growth.

Even in the disorderly age that followed the collapse of the Han empire there was produced a multitude of ingenious mechanical contrivances that reduced the labor of the more fortunate farmers and increased the yield of their lands. A moldboard was added to the plow, ox-drawn carts seeded the fields automatically, complicated harrows prepared finer seedbeds and water-powered mills made more flour with less human lobor.

The peasant was not only the backbone of the Chinese economy, he was also the muscle of Chinese power: he grew the food and he also fought the battles. In war, as on the farm, his equipment improved as Chinese culture advanced.

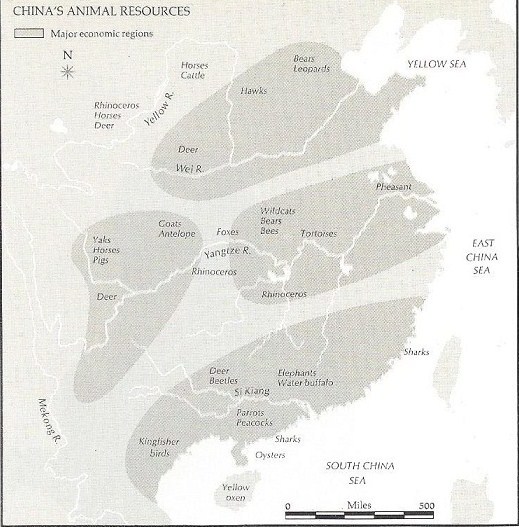

The men who went into battle to extend the rule of the kings of Shang and early Chou times wore armor made of the hide of buffalo or rhinoceros and carried “compound bows,” reinforced with horn and sinew, that shot arrows armed with points of bone or bronze. But their chief weapon in hand-to-hand combat was a simple halberd with a bronze blade. Somewhat later, in the Fifth Century B.C., soldiers were equipped with two-edged swords usually of bronze, though some may have been of forged iron.

Soon after, when the Chou feudal states were fighting desperately among themselves for supremacy or survival, innovations in military equipment multiplied, many of them originating among the northern steppe-dwellers. Regular troops of infantrymen and cavalrymen became more important than the patrician charioteers who had borne the brunt of battle in earlier times. The new horsemen wore barbarian trousers and boots, Scythian caps and gilded belt buckles-all quite un-Chinese. Foot soldiers along the northern walls now depended on powerful crossbows with bronze trigger mechanisms, and many men carried pellet bows that shot vicious little slugs rather than arrows. Such soldiers as these made up the victorious armies of Han that subdued a considerable part of Asia.

Military equipment underwent little change after the collapse of the Han empire, when most warfare consisted of conflicts among little states whose chief weapons were chivalry and deceit. Nonetheless, some new mechanical devices appeared then, such as magazine crossbows and multiple ballistics large, mounted crossbows-which were useful in the siege warfare that was the order of the day in the fragmented realm.

A farmer who was conscripted for war had little hope of resuming his normal life. The ordinary militiaman could expect to bleed on the hot sands of the northwestern deserts, or even-in civil wars -on the good yellow earth. Capture was no guarantee of survival. Victorious generals liked to enhance their reputation for ferocity and to chill the hearts of future enemies by the mass execution of prisoners. The First Century writer Wang Chung reports that officers of the ancient state of Ch’in, which was eventually to conquer all China, buried alive 400,000 soldiers of a rival state.

With better luck, a soldier might become a farmer again, but not necessarily on his own land. After Han times, the practice of establishing military colonies on unstable frontiers became increasingly important and seed, plows and oxen were supplied by the state. There, semi-professional warriors were expected to protect their farms and families against all invaders. But, in difficult times, they sometimes made common cause with their barbarian neighbors, with whom they often intermarried. With the re-establishment of social order by the medieval T’ang Dynasty, the land and the people flourished, and the mighty rulers conscripted farmers’ sons by the thousands to extend the rule of the emperor into the remotest parts of the continent. Their bones fertilized fields that their fathers had never imagined.

The T’ang armies could boast somewhat more efficiency and much greater elegance than their predecessors. Although the simpler soldiers still wore hide armor, and sometimes only breastplates of wood, felt or paper-the best soldiers were provided with iron-plate armor, sometimes gilded, or with the fine chain mail recently introduced from the Iranian west. But their weapons were not much changed. Bows were made of the resilient wood of the mulberry, or of the Palmyra palm of the far south. Although some arrows were now tipped with steel, they were only improved versions of ancient missiles. Still, the best swords were far superior to the old ones. Their blades were made of steel that was strip-welded to make them exceptionally tough and give them a beautiful damascened appearance – a process learned from India, it seems-and their shagreen-wrapped hilts were decorated with gold, silver or rhinoceros horn.

For the privileged classes of Han and T’ang, military life offered excitement and danger under exotic skies. Aristocratic young Chinese officers, armed with their new weapons and clothed in brocaded gowns and hats of marten fur, left their wives and sweethearts to fight the nomads on the edge of the Gobi Desert. As described in a Ninth Century poem:

They swore to sweep the Hsiung-nu away, without regard for their own persons:

Five thousands of them, in sable and brocade, lost in the Hunnisn dust!

Pitiful without a resting place-those bones on the river’s edge:

They are still live men in the dreams of distant boudoirs.

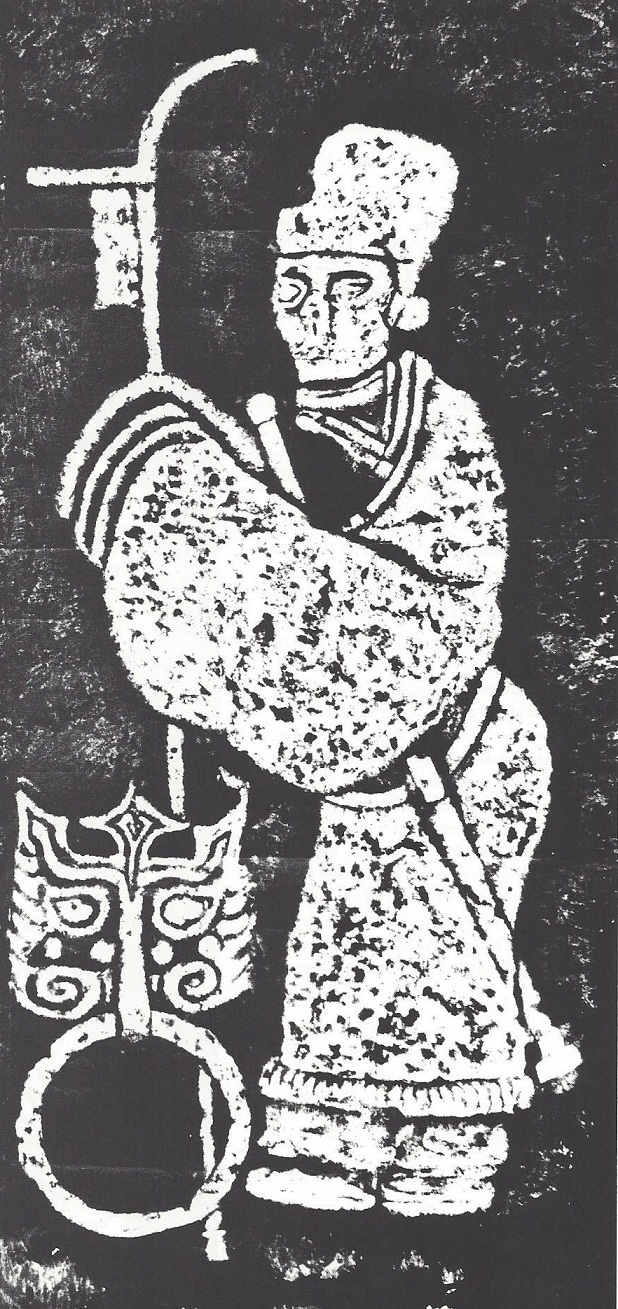

Guardian of a Tomb, this ceramic warrior, armored and ready with a sword, was buried with a well-to-do Chinese long before the T’ang Dynasty was founded in 618 A.D. The figure was placed in the tomb to ward off evil spirits and vandals who might violate the grave.

Yet death on the battlefield was perhaps preferable to the lot of the captured, who, when spared execution, were almost always condemned to slavery. Despite occasional abortive attempts by humane monarchs to abolish the commerce in slaves, the institution of slavery itself was never loudly or effectively challenged. Prisoners of war were only one source of supply. Great numbers of slaves were Hua men. Some of them were whole families condemned for a crime against the state by one of their relatives; others were men who had been sold by themselves or their families to pay debts.

In T’ang times, thousands of nomads from Mongolia and Central Asia, captured in the wars with China, were used as horse-herds, grooms, falconers and outriders to the carriages of Chinese noblemen. A few of them-expert potters, weavers or musicians-might become the gifts of the emperor to great vassals and rise to substantial positions. Unskilled war captives were herded into the feverish jungles, where they died in droves working to make the land habitable for their Chinese masters.

Many female slaves were entertainers, the Chinese counterparts of the Japanese geishas. In Chou times, women were sold publicly to private persons, and there were also state courtesans whose talents were required at parties given by the great lords. By the Ninth Century, in the capital of Chang-an, officials of the T’ang bureaucracy as well as young candidates for public office thronged the geisha quarters that were close to the national administrative offices. The girls themselves learned popular arts under rigid discipline; the most successful of them were not only beautiful and talented but also gifted in witty repartee. Some attracted the devotion of eminent personages.

More is known about the slaves and peasants of Ancient China than about the merchant class. The classical scheme of things did not acknowledge their existence at all. Traders and shopkeepers had always been viewed with mistrust by the privileged classes of China; the few merchants mentioned in Chinese literature are usually foreigners.

Merchants were allowed only a small, carefully supervised role in the transfer of everyday commodities. The finest and most expensive goods glassware, drugs, gold and incense-were brought to the imperial court by vassals of the ruler, or their emissaries, in the form of “tribute.” This was balanced by reciprocal “gifts” from the emperor to the humble contributor. This elaborate system of tribute to the emperor left no room for serious competition from the would-be entrepreneurs. As for basic products vital to the economy-such as salt, iron, wine and tea-imperial agents took charge of their production and distribution. Indeed, the salt and iron monopolies were mainstays of the imperial budget.

We still know very little about ancient shops and shopkeepers, the purveyors of the many everyday necessities produced by farms and workshops for the common man. We are best informed about the great public markets of the medieval capital city of Chang-an, which contained specialized warehouses and bazaars dispensing objects of bronze, leather, silk and wood. and were enlivened by street acrobats, storytellers and every kind of strolling foreigner -Persian gem-dealers, Turkish pawnbrokers and many others. We hear frequently of drug shops, and of vendors of cakes and sweetmeats. There were places for relaxation with cups of tea or wine. But we do not know how one bought pickles or baskets or shoes.

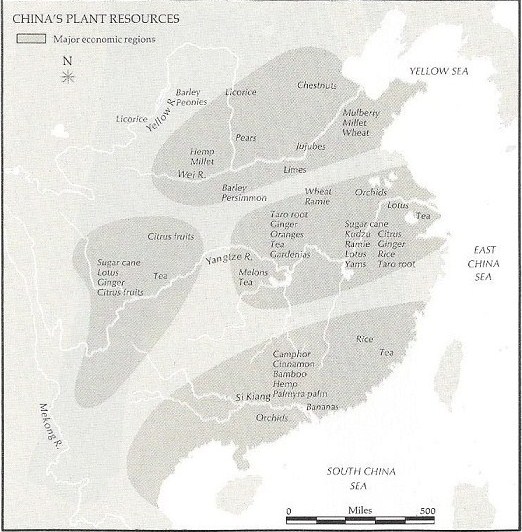

The product most sought by the city shopper was millet, the grass cereal that had been the staple of Chinese diet since earliest times-Confucius must have subsisted chiefly on millet cakes and dried beef. Wheat and barley cakes became common later, and even a poor man might augment his meal with beans, turnips and melons, flavor it with onion, ginger or basil, and top it off with peaches, plums or persimmons. If a man were moderately well off, he might occasionally add a bit of pork or chicken to this menu. For settlers in the south, rice became the staple, and was supplemented by taro root, grown-like rice-in flooded fields. A poor peasant or a traveler in the drier southern uplands might occasionally eat yams. Subtropical orchards supplied tasty oranges and tangerines, and the adventurous newcomer to the south might steel himself to the strange flavors of bananas, sago, coconuts and stewed frogs. A characteristic feature of the Chinese diet, which seems to have developed mainly after Han times, was a preference for all kinds of pickles and preserves, as well as fermented sauces and relishes, based on fish, shrimps, meat and beans.

By medieval times new edible plants unknown to the classical age were added to the Chinese cuisine: spinach came from the far west, as did pistachio nuts; dill was brought in from Indonesia; almonds from Turkestan. There were hundreds of other novelties. The gourmets of T’ang had developed an appetite for flavors that would have repelled their simpler ancestors. Cultivated northerners prided themselves on a refined understanding of the properties of various kinds of native mushrooms and on a taste for odd country dishes, such as wine-marinated white carp and steamed shoats in garlic sauce. They ate dumplings shaped and flavored like 24 different flowers, fluffy wheat steamed in baskets, “snow babies” made of frog legs and beans, and a kind of ice cream-a chilled mixture of milk, rice and camphor.

The Chinese equivalents of the popular beers and wines of the ancient Western world were the fermented products of the home-grown cereals, especially millet and rice. All men, great and small, rejoiced in these beverages. But there were more exotic drinks: grape wine for the fashionable party; coconut milk for the refreshment of melancholy exiles in the tropical jungles; palm toddies to take the thoughts of southern administrators away from the threats of malaria and poisoned arrows.

The pleasures of wine drinking are alluded to frequently in Chinese literature. The great T’ang poet, Li Po, is famous both as a drinker and as a writer about wine. One of his poems expresses, in a humorous but slightly macabre vein, his concern for a recently deceased wine merchant, Old Lao. The old man descended to the “Yellow Springs” and the “Terrace of Night” under the earth, and Li Po, left behind in the land of the living, wonders if a customer comparable to himself can be found there:

Old Lao, down below in the Yellow Springs,

Must still be brewing his “Great Spring” vintage.

But without Li Po in that Terrace of Night,

To whom can he be selling his wine?

During the unsettled post-Han age, China became familiar with a new nonalcoholic drink. Confucius never tasted tea, and it is doubtful that Wang Ch’ung, six centuries later, did either. The leaves of the tea plant, a close relative of the camellia, were first gathered in the warm south, probably by barbarians, to be brewed in water for a hot, strengthening drink. By T’ang times the novel beverage was becoming popular in the north, especially among the elite classes, and white and pale blue porcelain teacups were being made for the tables of connoisseurs. Formalities grew upon formalities, and, by the Ninth Century, a stylized cult of tea preparation and drinking existed in most parts of China-as it still does in Japan today.

Beauty and formality are seen also in traditional Chinese costume. The elite had worn silk, made from the cocoons of the world’s first domesticated silkworms, as long ago as Shang times. Simpler men managed with lesser materials, but the skilled Chinese made fine fabrics-almost as fine as silk -from woven vegetable fibers such as hemp, ramie, kudzu and banana.

The basic costume was established by the early classical period, the Sixth Century B.C., and consisted of a two-piece outfit-a long tunic, usually belted or sashes, topped by a jacket. The design was the same for all classes, but the materials and the refinements of detail varied in accordance with the wearer’s position. For ritualistic occasions most men wore additional outer garments of mystic colors and symbolic patterns.

The men of classical China were particularly proud of their shoes, which distinguished them from barefooted barbarians. Peasants wore straw sandals, but the upper classes had fine cloth slippers, often of heavy damask or brocade.

At the end of the Chou period, in the Third Century B.C., this costume began to be modified by influences coming from the northern nomads. Underpants, leather trousers, leather shoes and leather belts with gilded and jeweled hooks in the vigorous “animal style” of the steppes became popular. By medieval times, other outside influences were reflected in further innovations; the ladies of Tang were proud to appear in public in the latest Turkish and Iranian styles.

Hair dress was particularly subject to the vagaries of fashion. The traditional men’s headdress was a simple hat or kerchief, but by Tang times a top-knot wrapping of some kind or a gauze cap stiffened with lacquer was popular. Men and women alike wore gold and gems on their heads-even men required elaborate hairpins to hold their topknots in place and the women balanced tinkling golden crowns decorated with pearls and precious stones.

Upper-class women owned little compartmentalized boxes, provided with mirrors, in which they kept their cosmetics. These included rouge, colored with safflower or cinnabar, for their lips and cheeks, white lead or rice powder for their faces and shoulders and blue, black or green grease for the manufacture of illusory eyebrows. Eyebrows were at all times subject to the whims of fashion: sharp-pointed tops were the vogue in the Second Century B.C. and curved arches in the Second Century A.D.; there were “sorrow brows” in late Han times and “distant mountains” in Tang. Mouches appeared on ladies’ faces at the end of Han; yellow foreheads had their heyday in Tang.

In Ancient China, both peasant and king lived in the same kind of house. Even the most imposing buildings were only exaggerated farmhouses: a manor, like a farm, consisted of a courtyard with a gate in its south wall (the direction of holiness), a complex of buildings within the yard, a main dwelling in the center and a garden behind. The number and kinds of buildings varied enormously from one courtyard to another, and of course the materials and the decorations of a royal palace or a holy temple were incomparably more elegant and durable than those of a farmhouse. But the basic differences were slight.

From the earliest times the walls surrounding the house complex were made of rammed earth, and individual buildings were erected on rammed-earth foundations. The buildings were simple rectangular structures with roofs supported by rows of wooden pillars based on stone plinths. Spaces between the pillars were bridged above by horizontal timbers, and were usually filled in with plastered earthen walls. In the earliest times, roofs were made of thatch-the first roof tiles did not appear before Chou times. Wood was always the basic building material; stonework was used only on public and religious structures-for an occasional elegant pavement, balustrade, staircase, platform or burial chamber.

Chinese building techniques were conservative, and the innovations were minor; once introduced, however, they tended to become permanent. Among such changes were the elaborate sets of brackets that were developed in late classical times to support the long projecting eaves that had replaced the simple capitals topping the pillars of antiquity. By Tang times, the shadowing eaves began to turn upward in graceful curves-an architectural feature now regarded as typically Chinese.

The oldest of the great Chinese buildings-the pride of the Bronze Age-were decorated with images, probably religious or magical, done in red and black lacquer, which was then the chief medium of painting. By Han times the walls of important public buildings were painted with edifying scenes from the lives of the ancient sages and kings. Gilded pillars, window frames adorned with bits of mica and colored glass, vermilion rafters and marble staircases enhanced the beauty and dignity of upper-class houses of Han and later times. But the framework remained the same through the ages: a hall of wooden pillars and lintels set on a foundation of earth and stone.

The amenities inside the great houses became steadily more elaborate. Even after the fall of the Han Dynasty, during the age of division, a few rich and powerful men could install unparalleled luxuries and conveniences in their homes. Consider, for example, the fantastic court of Shih Hu, who reigned over the small northern state of Chao during these times. Shih Hu was a complicated man. He was a barbarian, a skilled archer and hunter, descended from some wandering shepherd from the northern steppes, yet his chief adviser was a learned Buddhist monk, and under his rule the gentle faith of Buddhism was permitted to flourish. He was a violent man-his given name “Hu” appropriately means “Tiger.” In his splendid palace he had all-girl orchestras and battalions of female soldiers clad in sable furs, wearing golden rings and carrying bows painted yellow. Late in life he became very fat, and had to be carried to the hunt in a litter borne by 20 men. It contained a revolving couch from which he could shoot in any direction.

This ingenious litter was typical of the man, his capital city and his palace. It boasted a handsomely painted bathhouse, where water spewed from the mouths of nine dragons into a great jade basin and drained away through the mouth of a bronze tortoise. Another building was equipped with air-conditioned summer rooms, cooled by ventilators connected to ice-storage pits. Among many mobile mechanical contrivances were a cart bearing a man-like figure that always pointed in the holy southern direction, and another surmounted by an image of the Buddha, which was constantly laved by water spurting from the mouths of dragons and scrubbed by a group of wooden monks.

By the Ninth Century, prosperous households in the capital city of Chang-an were equipped with baths, heaters, mechanical fans, artificial fountains and ice-cooled rooms. In these times, the villas of some aristocrats boasted “pavilions with automatic rain,” and one medieval emperor had a large hall that was completely air-conditioned. A favored guest of the monarch’s described a whirling fan that sprayed water behind the royal throne, from which blew a cool artificial breeze. The guest was invited to sit on a stone bench that was cooled from within, and he sipped an iced drink as he watched the curtains of water that fell from all four eaves of the building.

The typical house of a well-to-do T’ang family was decorated with furniture and accessories made of wood, metal, lacquer, glass and ceramics. Wooden articles included spoons and chopsticks of fine-grained jujube, writing brushes of bamboo, and perhaps a harp of paulownia wood. The family might own a bronze mirror, its back inlaid with amber and turquoise; ewers and goblets of hammered gold and silver; and dishes made of fine porcelain or blown glass. The favored colors for these wares were the colors of the best jade-white, pale blue or green. A cultivated gentleman of the Ninth Century, admiring his teacups, would have remembered this sentiment:

Porcelain of Hsing is akin to silver,

Porcelain of Jeuh is akin to Jade

High-born Chinese ladies and gentlemen, waited on by corps of servants and slaves, whiled away their leisure in various entertainments. They enjoyed sports, parlor games, music and dancing, and the great seasonal and ceremonial festivals that marked such occasions as the new year-or the emperors birthday. Some of these amusements were shared by the lowliest common folk. Hunting, for example, was a sport indulged in by everyone. A royal hunt was a grand affair, with beaters, dogs, cheetahs and eagles. But even a lesser nobleman might enjoy a day on the plains with a trained Korean falcon, and a commoner could take his goshawk into the forest with the hope of adding a hare or pheasant to the family pot.

There were other active sports, including a kind of football that had been popular since antiquity and that was regarded as a useful military exercise. In T’ang times, emperors, courtiers, scholars and even ladies enjoyed the game of polo, which had been introduced riot long before from Iranian lands. Persian horses from Iran were in fact greatly prized in China by polo players, soldiers and sportive aristocrats. Brought to China in Han times when the Han armies opened the west, and attached to the emperor’s stables to augment the royal herd of Mongolian ponies, Iranian horses had a special glamor and were known as “dragon horses” or “horses of heaven.” T’ang poetry is full of allusions to them.

Among the less active sports were board and table games, some of which were distantly related to modem Parcheesi, lotto and backgammon. One very ancient and very popular board game, now becoming known to Americans under its Japanese name of “go,” had overtones of military strategy. Playing cards are also thought to be a Chinese invention of the T’ang period.

Dancing was inseparable from life, religion and all ceremonial acts. The ancient kings had danced to appease the drought demons of Shang times, and in the time of Confucius, troupes of barbarian dancers twirling yak tails and wands tipped with pheasant feathers performed in the courts of the kings to drive away evil spirits. Some magical dances such as these were still being performed in the courts of the emperors of T’ang, but, by medieval times, there were also dances that were performed purely for the entertainment of sophisticated audiences. The wild gallops of the Turks and the Iranians delighted upper-class T’ang gatherings. Another extremely popular dance was the specialty of Sogdian twirling girls; they performed it on the tops of large rolling balls while attired in costumes of green pantaloons and crimson robes.

Music, an inseparable part of dancing, was at the same time considered a much more serious pursuit. The Chinese men had always believed that music had mystical and moral properties. Confucius and his followers held that certain kinds of music were elevating and purifying, while others led to corruption and depravity. Accordingly, music was put high on the list of required subjects in the education of gentlemen.

The most holy and venerable of musical instruments, revered perhaps even beyond the great bronze bells that rang in court and temple, were sets of stone chimes-triangular pieces of limestone that were suspended in racks and struck with batons. These were sounded in the sacred orchestras of Shang, and were still being played in the classical ensembles of T’ang. Drums, bells and flutes were also ancient and respected instruments. Stringed instruments were less highly regarded, except for a certain kind of zither, the music of which was thought to be especially suitable to the meditations of respectable gentlemen. Harps and lutes, which became very popular after their introduction from western Asia in Han times, were generally used on informal, relaxed occasions. A unique instrument was the sheng, a kind of mouth organ made by inserting a set of canes into a gourd; apparently it originated among the peoples of Indochina. It found its way to Europe in the 18th Century and influenced the development of organs, harmonicas and accordions.

Music and dancing formed the core of the most colorful and exciting of all entertainments-the great palace-shows, such as might be given on the occasion of an imperial birthday. At celebrations of the emperor’s birthday in the early Eighth Century, the festivities were enlivened by a troop of a hundred dancing horses adorned with rich silks and precious stones and metals. They danced with tossing heads to popular tunes played by the palace orchestra. On the same occasions there were also displays of the tricks of foreign magicians, musical performances by bands of richly dressed palace girls and parades of elephants and rhinoceroses.

In addition to such special national celebrations, there were the eternal but ever-changing seasonal festivals, made meaningful by ancient beliefs, in which the lowliest clodhopper could find occasions for joy and the reaffirmation of faith. The end of winter and the beginning of spring, for instance, signalizing every sort of spiritual and physical renewal, each produced a series of festivals, including salutations to the local earth-gods and mating and fertility rites. The whole cycle of months had a corresponding sequence of holidays, such as the brilliant street illuminations during the first month. After the introduction of Buddhism in the First Century, there were also outdoor spectacles, subsidized by the great monasteries of the major cities, portraying episodes in the history of that faith for the edification of the public.

These festive rites and gay celebrations, enjoyed by the people of all classes, were the bonds that crossed the division of society and united all Chinese into one great civilization.

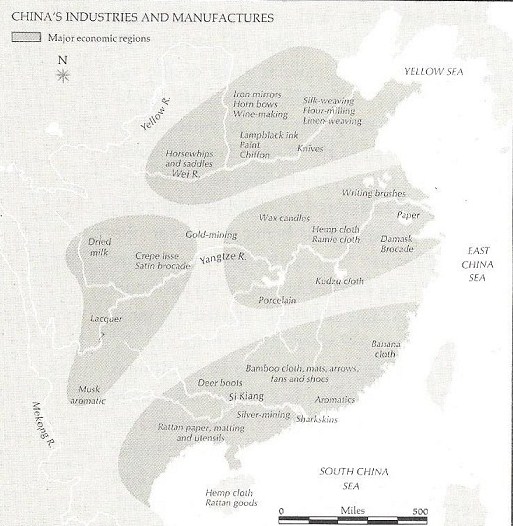

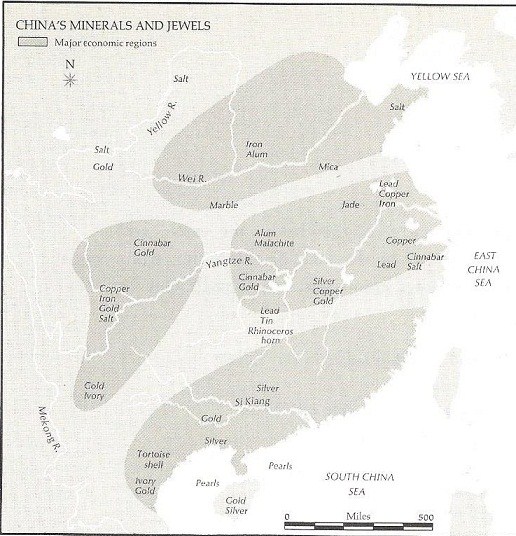

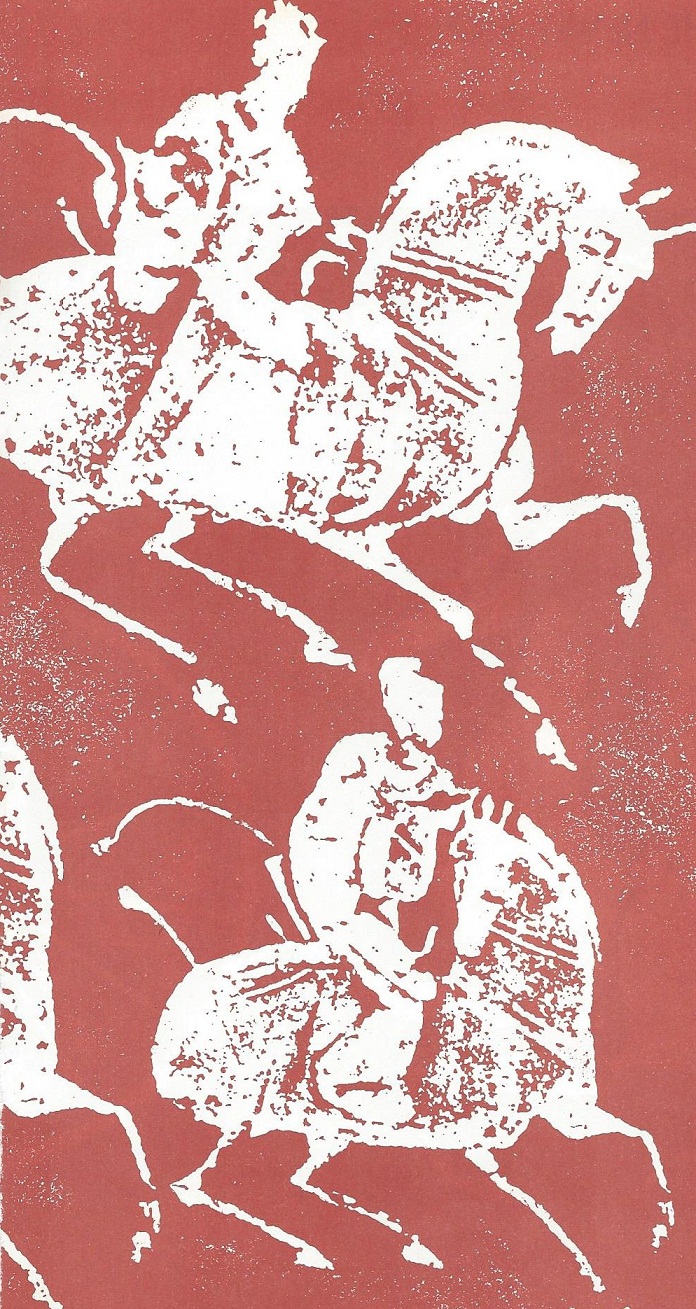

Frontier lords and peasants

During the illustrious centuries of the Han Dynasty (206 B.C. to 220 A.D.), daily life in China was recorded in bas-relief on tiles and stones made for the tombs of wealthy men. Some of these sculptures, like the large halberd-wielding figure at right who guarded the tomb from evil spirits, had specific religious meanings.

During the illustrious centuries of the Han Dynasty (206 B.C. to 220 A.D.), daily life in China was recorded in bas-relief on tiles and stones made for the tombs of wealthy men. Some of these sculptures, like the large halberd-wielding figure at right who guarded the tomb from evil spirits, had specific religious meanings.

But many others, designed to entertain the deceased, were purely secular renderings of hunting and fishing, huts and palaces, soldiers and jugglers-all the men and occupations of a vigorous world. China under the Han was vigorous indeed.

For the first time, the country was truly unified-a single, vast state, infused by a common culture. Even in the remote western region of Szechwan, district officials aped the manners of the imperial court, and peasants built their homes and ploughed their fields in fashions that prevailed throughout China. The most extensive visual records of the period are the sculptured reliefs in Szechwan’s tombs, and ink rubbings of these reliefs, like the ones shown on these pages, portray Han life with irresistible vivacity and truth.

The Hard Life of The Peasant

Szechwan was one of the most fertile regions of China, yet the iot of its common folk was generally difficult. He and his family usually lived in a drafty one-room house with a tile roof, a dirt floor and no furniture.

Szechwan was one of the most fertile regions of China, yet the iot of its common folk was generally difficult. He and his family usually lived in a drafty one-room house with a tile roof, a dirt floor and no furniture.

Half his crops went to the landlord who owned his fields and another large part to the government; to feed his family, he had to trap small animals and catch fish-and during some periods of the Han Dynasty, even the fish were taxed.

In hard times, a peasant’s life was nearly unendurable. During the first 200 years of the Dynasty, such disasters as droughts, floods and wars struck no less than 20 times, forcing peasants to sell their children into slavery, kill their babies because they could not feed them, and even resort to cannibalism.

And at just such times of calamity the government often tried to replenish its own shrinking coffers by raising taxes-a practice that gave rise to the proverbial Chinese saying, “An oppressive government is more terrible than tigers.”

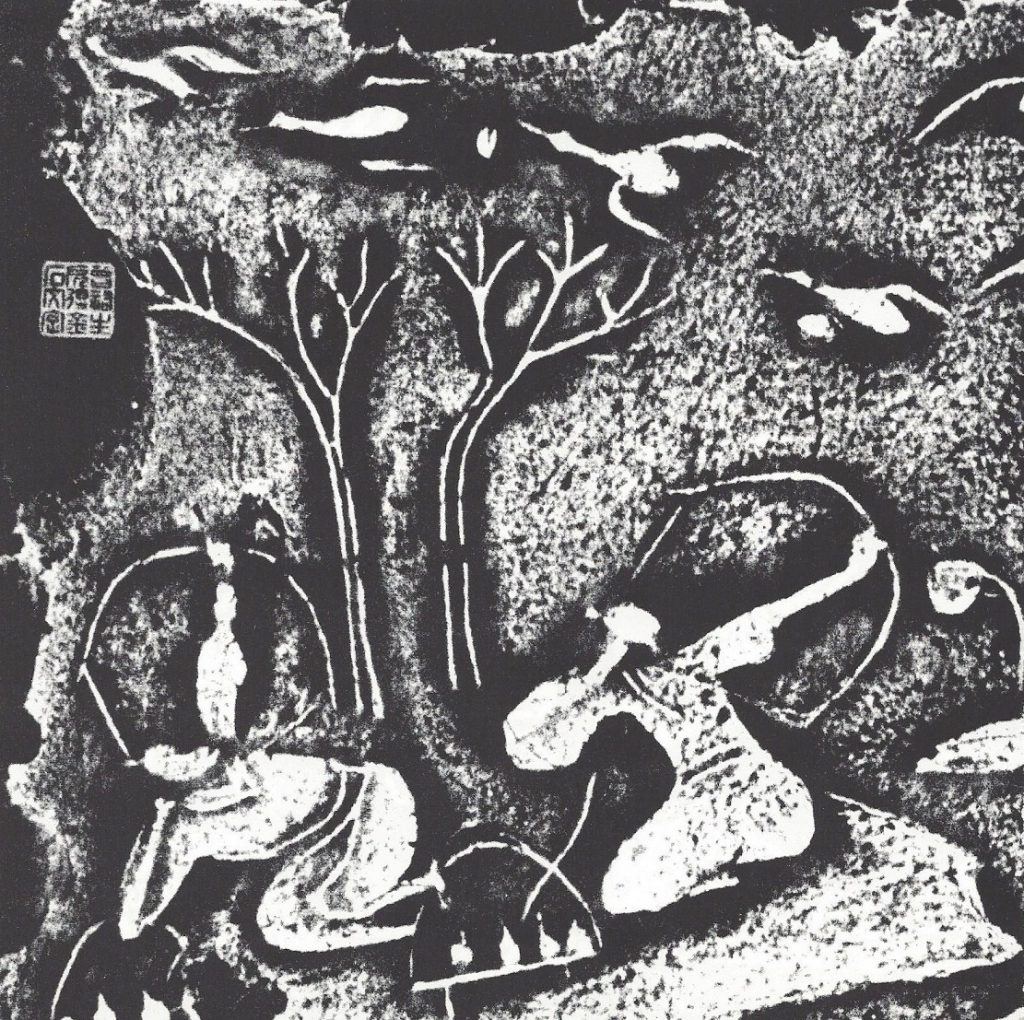

The Gentlemanly Sports of Archery and Hunting

Archery was one of the traditional accomplishments of a Szechwan gentleman, along with writing, chariot driving and a knowledge of music and ceremonial etiquette.

Archery was one of the traditional accomplishments of a Szechwan gentleman, along with writing, chariot driving and a knowledge of music and ceremonial etiquette.

According to Confucian precepts, gentlemen displayed their skill as archers on three hunts a year, in the spring, autumn and winter. In this rubbing, two hunters draw their bows at a flock of geese overhead.

Any sort of hunting must have been particularly rewarding in the Szechwan forests, for they abounded with quail and pheasants, foxes, deer and marmots. The gentlemanly hunter, however, never tried to bag too large a kill. If he used beaters to flush game, he placed them on only three sides, leaving the fourth side as an avenue of escape for the animals.

Noble Steeds for the Emperor the Emperor

Harried relentlessly by barbarians from beyond its borders, the China of Han times was constantly at war. Lightning cavalry raids by the Hsiung-nu of the north were a constant threat. To repel such attacks the Chinese needed a sizable cavalry, but years of civil war had decimated the nation’s supply of horses. The supply was so low, in fact, that the first Han emperor could not in all his empire locate four horses of the same color to pull his chariot.

Harried relentlessly by barbarians from beyond its borders, the China of Han times was constantly at war. Lightning cavalry raids by the Hsiung-nu of the north were a constant threat. To repel such attacks the Chinese needed a sizable cavalry, but years of civil war had decimated the nation’s supply of horses. The supply was so low, in fact, that the first Han emperor could not in all his empire locate four horses of the same color to pull his chariot.

One great reservoir of horses to fill China’s empty stables was Ferghana (present-day Turkestan), which raised magnificent steeds like those shown at left. One Han emperor sent 60,000 men to Ferghana to seize horses by force, and married off one of his own female relatives to a barbarian king in exchange for 1,000 horses.

Once obtained, these horses were bred at 36 stations in such frontier regions as Szechwan. Though the breeding program eventually produced more than 300,000 horses, a good mount was still so valuable that it could be sold for 300 pounds of gold.

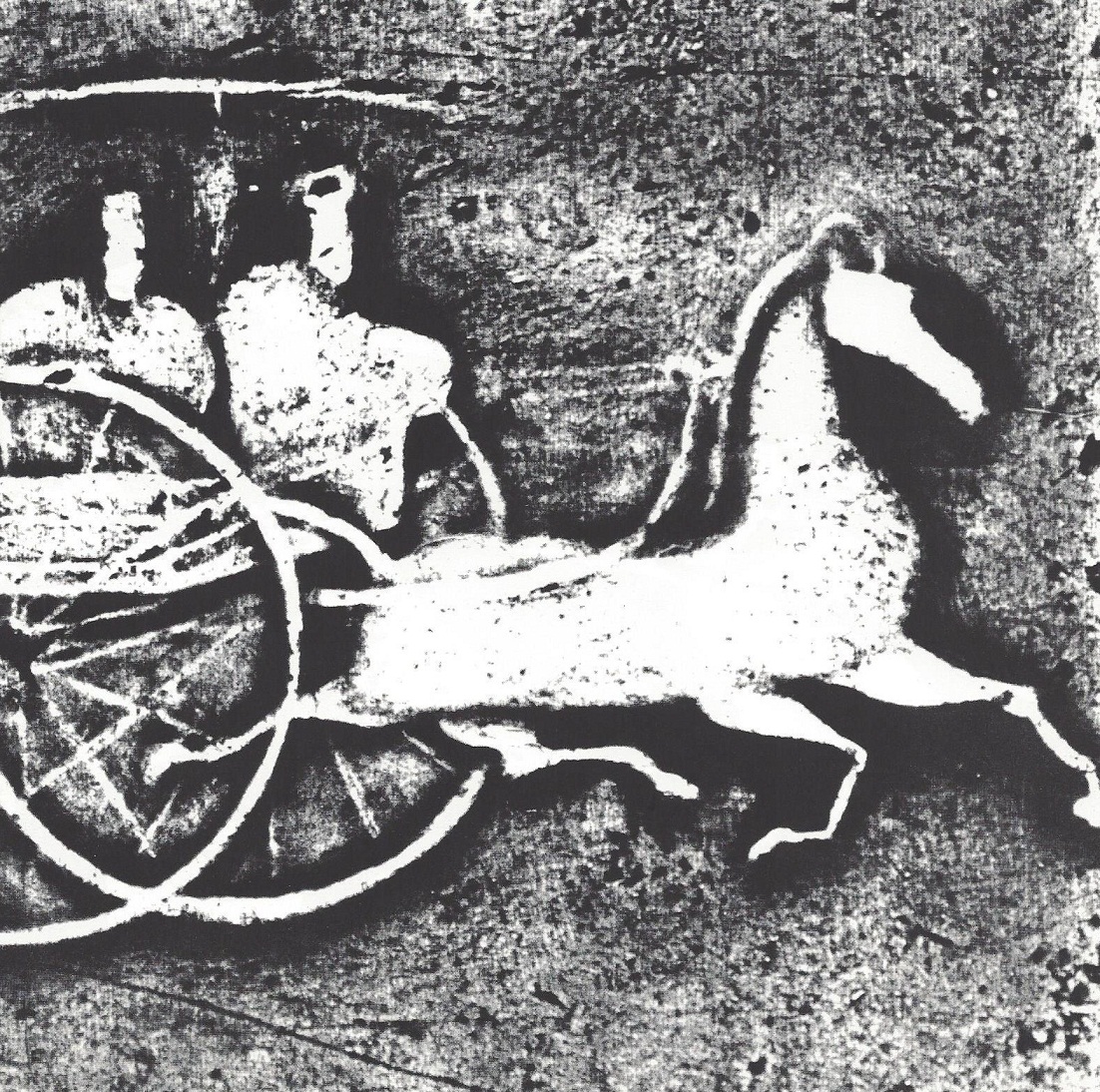

The Pretensions of the Newly Rich

Szechwan produced lacquered ware, brass utensils, dyes and silks, and its mines were a major source of salt and iron. Some men derived immense wealth by trading in these commodities.

Szechwan produced lacquered ware, brass utensils, dyes and silks, and its mines were a major source of salt and iron. Some men derived immense wealth by trading in these commodities.

A really successful merchant rode in a cart with a coachman and an outrider (below), bought an honorary title from the emperor and built a mansion surrounded by gardens and pools.

Such ostentation in mere commoners so infuriated officials and farmers that the government enacted laws against extravagance -at times it was illegal for commoners to ride in a chariot of any kind-and one writer denounced tradespeople who “neither plow nor weed,” but “ride in well-built cars and whip up fat horses, wear shoes of silk and trail white silk behind them.”

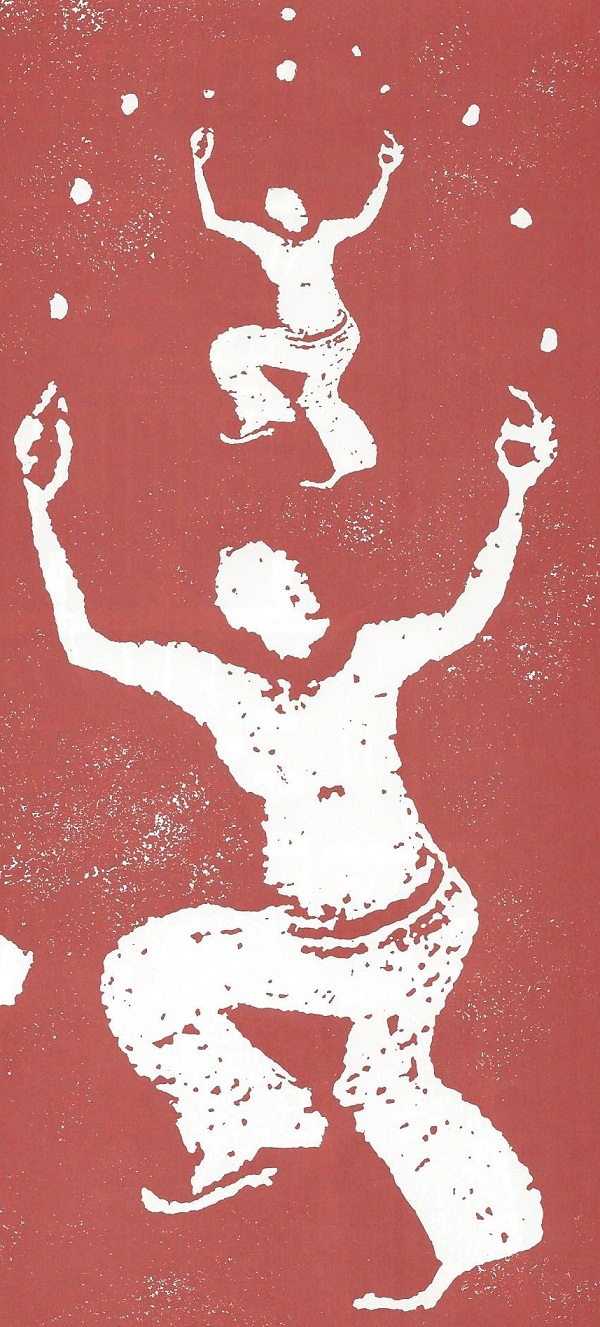

Revelries at a Feast

A large-scale feast was an occasion that brought all the Szechwan gentry together in an orgy of food and lavish entertainment. In fact, such feasts were so popular and disruptive that the government was forced to restrict them to holiday seasons; at all other times it was against the law to have more than three guests to dine.

A large-scale feast was an occasion that brought all the Szechwan gentry together in an orgy of food and lavish entertainment. In fact, such feasts were so popular and disruptive that the government was forced to restrict them to holiday seasons; at all other times it was against the law to have more than three guests to dine.

Partly because feasts were so rare, the hosts spared no expense. They ordered the most exotic and expensive dishes-snails preserved in vinegar, dog meat, turtles and slices of raw meat seasoned with ginger and topped with ant eggs.

Troops of professional performers were hired to juggle and dance to the music of drums. Liquor was dispensed so freely that guests often rose from the audience and joined in the dances.

Such behavior led one poet to complain about unruly revelers who “keep dancing and will not stop,” reeling about “with their caps on one side, and like to fall off.” “Drinking,” the author primly concluded, “is a good institution only when there is good deportment in it.”

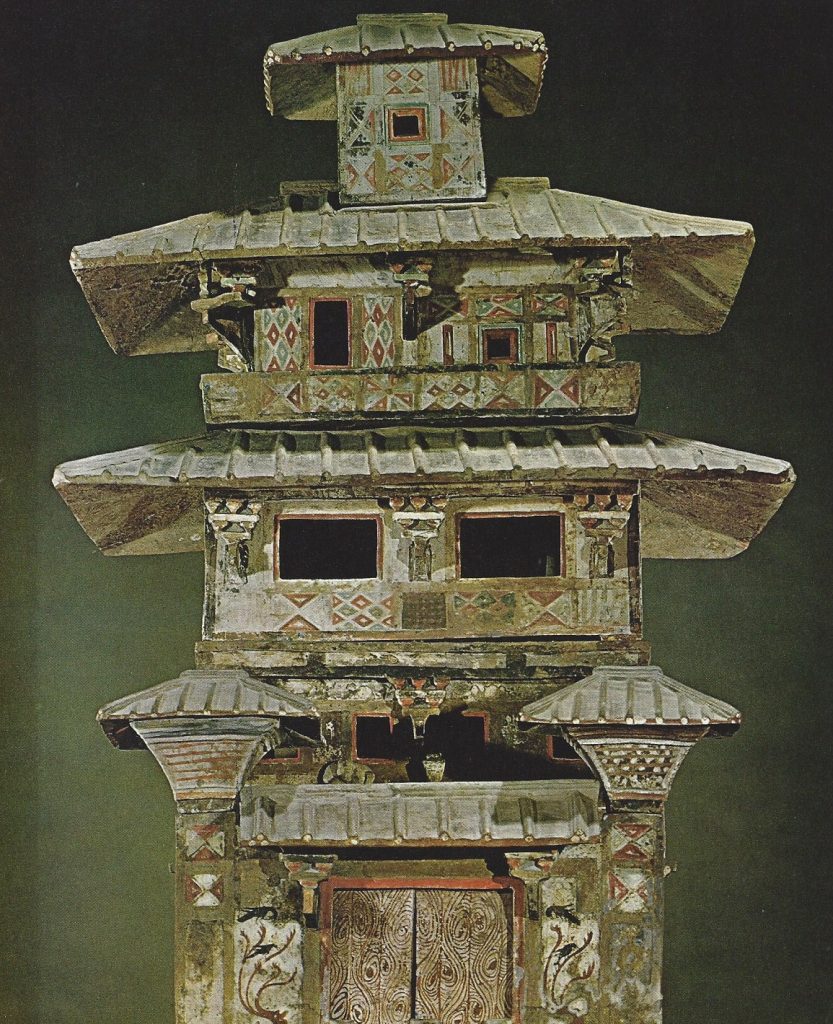

Architecture for an Imperial Age

No buildings erected during the Han Dynasty are still standing, but reliefs like the one at the right testify to their grandeur. The relief depicts a monumental gateway, flanked by memorial pillars and topped by tiled roofs and the figure of a mythological bird-the phoenix.

No buildings erected during the Han Dynasty are still standing, but reliefs like the one at the right testify to their grandeur. The relief depicts a monumental gateway, flanked by memorial pillars and topped by tiled roofs and the figure of a mythological bird-the phoenix.

In the early days of the Han Dynasty, architects concentrated on imperial palaces-perhaps because, as one builder explained, “without great size and beauty” the emperor’s residence “would lack the means of inspiring awe.”

But rich citizens soon rushed to imitate imperial splendor. They built sumptuous homes decorated with sculpture, paintings and costly draperies, and imported cashmere carpets.

They even furnished family tombs with carved pillars and stone lions and added inscriptions mentioning how much each item had cost. After the collapse of the Han Dynasty, several centuries of conflict brought a decline in architectural; but when China finally recovered, the new empire took the vanished glories of the Han, as its models of magnificence.