The far north west of China has fairly recently been opened as a tourist area. This is desert land – around 100,000 square miles of the Taklimakan Desert, said to be the second largest desert area in the world. It provides an exciting holiday destination that is very different from the rest of China.

If you take a trip there, you will travel on hot, dusty roads, but as well as stark rocks, sand dunes and mountains, in some places you will see orchards and vineyards, and you will find out how the locals are able to produce them in such an arid land.

Tours usually begin at the north eastern edge of the desert, at the town of Urumqi, which has an international airport, though if you arrive on a long haul flight, you will probably have changed elsewhere in China first. Urumqi is the capital of Xinjiang Province, and there is nowhere in the world that is further away from the sea.

If you spend any time here, you can find information about the region and its people in the provincial museum, Xingiang Sheng Bowuguan. The architecture of the city reflects the spartanness of the Russian influence, but you will find several mosques and some lively bazaars.

For a birds eye view of the town, head for the summit of Hong Shan (Red Mountain). An attractive park with a pagoda and space for entertainment has been built there. Looking across the river to a twin peak at Yamalike Hill, you might be inclined to believe the legend that the two hills were created from a red dragon which was caught by the Empress of Heaven and cut in half with her sword.

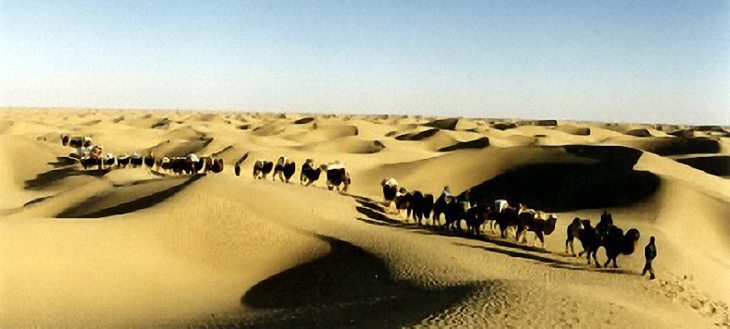

The edges of the Taklimakan are where the great Silk Road routes passed, and early meetings of people from the east and west took place. It was considered too dangerous to cross the shifting sands of the centre of the desert, but routes followed both the northern and southern perimeters. The easiest crossing was to the north, while the southern route, though more perilous, was shorter.

This desert’s temperatures are not always excessively hot and can be very cold at night. It is only protected from Siberian winters by the mountains to the north. And mountains all around provide water from rainfall and melting glaciers to several oasis towns.

The oasis town of Kashgar, (sometimes known as Kashi) in the far west is the point where this side of the northern and southern routes around the desert converge. As befits a Silk Road stop, Kashgar has a daily bazaar well worth visiting, while a special market every Sunday is enormous and attracts people from far and wide. Old Road is a street where you can see the products of local craftsmen in the making, and select the results you like best to buy and take home. Many different ethnic groups live here and pursue their traditional crafts. Among the many, you’ll see carpet makers, coppersmiths, blacksmiths, jewellers, makers of musical instruments and traders in silk and other textiles.

You might also have a chance to visit the tomb of a royal family, that of Abakh Khoja, a powerful 17th century ruler. The magnificent mausoleum building is known as the tomb of Xiang Fe, one of Abakh Khoja’s descendents who was a beloved concubine of Emperor Qianlong. She requested burial in her homeland and, although she also has a tomb in Beijing itself, the emperor sent a coffin full of her clothes to be delivered here. An ancient cart, said to be the original that was pushed for the three and a half year journey, can still be seen on the approach to the tomb.

A popular trip from Kashgar is to visit the crystal waters of Lake Karakuli. Transport will take you high into the Pamir Mountains, close to where they join the Tian Shan range to the north and the Kunlun Mountains to the south. At around 3,600 metres you come to the lake. This calm, glassy body of water, that perfectly reflects the snow covered peaks that surround it, is a breathtaking sight. You might be lucky enough to experience the hospitality of one of the yurts at the water’s edge.

Heading southeast from Kashgar, you reach Hotan, another Silk Road oasis known as the Ancient Kingdom of Jade and Silk. High quality white jade has been found in the Yurungkash River near Hotan since ancient times. Prospecting there has been so popular that the authorities have had to put regulations in place to protect the environment. But you can still visit the Jade Factory in the town, and if you go in the summer season you can see it being carved by hand in the workshop there.

You can also visit a silk workshop where you will witness the whole process of transforming the cocoons of silk worms into beautifully woven fabric, done in the traditional way, all by hand. This is in contrast to what happens in Hotan’s silk factory, where the process has been mechanised, making production speedier.

If you have time for an excursion from Hotan, you might choose to visit the Kokmarim Rock Cave about 21 miles from the town on the east bank of the Karakash River. The cave has two compartments one above the other with steps to connect them. The view from the top encompasses the fast-flowing river below and its green, fertile valley, with the distant mountains as the backdrop. The caves were first mentioned nearly 2,500 years ago in the ancient book, “The Note of Bhudda Countries” which is an important record of his travels by the Chinese sage, Faxian.

Hotan is a good base to visit a number of archaeological sites in the area. It is also a good place to witness the culture and way of life of the Uyghur people.

No trip to this part of China should miss the experience of crossing through the centre of the Taklimakan Desert. Tour operators offer a number of different ways to do this, so you could choose trekking on foot or riding horses or camels. But the easiest way is by road, and you could travel south to north for about 250 miles, on the longest desert highway in the world. Sit in comfort and look out on a magical landscape of shifting, crescent shaped sand dunes that can reach heights of up to 650 feet.

The oasis town of Kucha in the north can be reached in this way. The Grand Mosque in Kucha is the second largest mosque in the province. Thought to have been built originally in the 16th century by Isaq Wali, a devout muslim who founded Xinjiang’s Ishan Sect, it was unfortunately destroyed by fire, then rebuilt in 1931. The last Prince of Kuche, up until The People’s Republic was formed in 1949, was Daut Mahsut. Now over 70, he is often to be found telling stories for visitors in the Great Hall of this mosque. In Kuche you could also visit the home of an Uyghar family and see how life continues for a traditional farming family of the region.

Kucha has its own nearby Bhuddist caves and the Subash Ruins are only a short distance away. These are ruins of Guici, a former oasis town on the Silk Road’s northern route past the desert. Of the two sets of ruins, those in the east are much better preserved and are free to enter, but they have to be reached by a fairly long trek on foot along a dried up river bed across the desert. The road will only take you to the other set where an admission fee is charged. From here, if you clamber as high as you can, you will glimpse the far ruins on a plateau in the distance.

On your way back to Urumqi, you might visit the town of Turpan and its surrounding area. One excursion not to be missed will take you to see the karez wells in the Turpan Basin. These are a unique system of underground water works probably designed some time in the first few centuries BC. They are intended to make the most of the water that flows from the mountains to the north and west each summer when some of the high snow and ice thaws. Keeping the water underground stops it from evaporating and silting up with the sand that blows around in the wind. Water can be supplied to farmland throughout the year.

Only a few miles from Turpan itself, are the Jaiohe Ruins, which claim to be the best preserved of their kind in China. The name, Jiahoe, means a place where two rivers meet, and the town was built on an island at just such a place in the early AD years. The area, almost completely surrounded by mountains, was ideally placed for defence and there is evidence of earlier habitation as far back as the Stone Age. However, its strategic placement did not protect it from eventual destruction in the wars of the 14th century.

Visitors today can still make out the geography of the town and see ruined streets, alleyways, cave houses, palaces and official buildings, with over 50 Bhuddist temples and many underground passages.

A little more distant from Turpin, around 28 miles, is the location of the Kizilgaha Thousand Bhuddha Caves on the northern bank of the Muzat River. These are thought to be the oldest and most extensive in the country. Over 200 of them were hewn out of the cliff face and are richly decorated with murals and Bhuddist statues.

These are a few of the attractions of the Taklimakan desert area. You can find out much more if you take one of the organised trips or become an intrepid independent traveller of the wild north west of China.